|

| Sarah Riggs (c)UPEC/Nicolas Darphin |

Sarah Riggs, from texts

of Alan Halsey, Pascal Poyet, and Lisa Robertson

When the writer’s ‘I’

only appears alphabetically, what we have is a revolution. For what is implicit

in this choice of structure is an acceptance of how the text exceeds the

control of the indivudual. There is an

excess of motion beyond what a text declares to know. The words go into

orbit. The letter « I » will

come around again, by dint of the text’s alphabetic circulation, whether the

writer is there or not.

The text, in the case of

Alan Halsey’s «Towards an Index of Shelley’s Death » as announced in Revolution : A Reader, edited and

reread-by-marginalia by Lisa Robertson and Matthew Stadler, is a variorum composed

of various accounts of Shelley’s

« ending », including Trelawaney’s, Mary Shelley’s and Byron’s. It is

necessarily plural in its sources, and plural in its directionality. Its

relationship to ending is one of continuing, of ever-shifting.

Who is it who writes,

when the I comes around, in « Towards an Index of Shelley’s Death »

(are the answers important ? why have you even asked the question ?) ?

I am but as the shade of her

I dreaded not the tempest

I float down

Imageless

Intertranspicuous

Into a sea profound

Invulnerable nothings

The authors of a

revolution are readers. Revolution=a

reader. Alan Halsey is a reader of multiple

accounts that filter through him. In

this sense he is as a medium. He writes (is it he ?) : « The

teller is bound to the endless repetition of an evershifting story. »

In her currently

unpublished Cinema of the Present,

Lisa Robertson’s text reads :

You became strange, you

became my eyes.

I put my studies at your disposition.

You see small mammals

fighting in trees.

I see it on your face.

Periodically a building

will produce an exoskeleton of great vulnerability.

I see it on your face.

Is this the surface where

expression converts to love ?

I, Byronic, you said, fucked my way forward.

You were reading the city

wrecklessly.

The writing surface might

as well be water, for all that it is solid, who is « I » and who is

« you. » The text is

structured in one part, and not stubbornly consistently alphabetically, and

repeatingly, interspliced with lines. The lines of a conversation ? Must the questions be so two-dimensional when

the conversations are deeply dialogic ?

Stars and sun and moon look to each other differently from each angle,

at the various moments of revolution.

Then there

are lists. Sometimes, often, of three. Pascal Poyet finds them in Cinema of the Present, clusters them

together, into a present which is its own index. An index to a revolving book. Some, many,

most, of the clusters are his. Some are hers : « University, swimming

pool, botanical park .»

The list is like the

alphabet in that it equalizes, and renders liquid, the playing field. Renders plural. Each word resounds so particularly, is

particulate, there is no reckless accumulation.

« I, Byronic, you » Indeed we are fucked, and also in the most literal,

pleasurable way. A moving forward is a

moving backward and around, in and out. A marginal note by LR to

« Shelley’s Death » (by Edward John Trelawney, from « Records of

Shelley, Byron, and the Author ») reads :

The corpse evades identity ; only

its remnant accessories assist the

ritual of identification. The

24-year-

old Keats, whose book helped to

confirm Shelley’s identity, had died a

year earlier of consumption in Rome ;

first he had chosen his own epitaph :

« Here lies One Whose Name is writ

in Water. » The statement is usually

interpreted as an avowal of Keats’s

extreme bitterness over his lack of

recognition as a poet ; Shelley himself

believed that vicious criticism caused

the turn in Keats’s illness that quickly

lead to his death. But for me the epi-

taph points to Davenport’s time-like

sea again—the indifferent inevitabil-

ity of the dissolution of self. Reading

it I feel a relief.

Reading the dissolution

of self as relief. How were they able to identify Shelley’s body, wrecked as it

was by a literally watery dissolution ?

(Always this wish to identify, to pin down ?) In evidence, a volume of Keats’ poems opened

in the corpse’s breast pocket. Somewhere the revolution/reader tells us, I

can’t remember where or who. There is a constellation of texts, three of them,

I won’t list them for you, in this book

(revolution) which is not meant to circulate by the accustomed means,

relating to Shelley’s dissolution.

Whether it was Shelley’s

heart or liver which survived the ocean-side cremation. LR delights in the

liver. Whatever organ it was, so the text goes, Mary Shelley wrapped it in

Shelley’s poetry and kept it in her desk.

The body of the text is

inscrutable. No « eye » sees retinally ; no one « I »

can be identified. Yes. This is a relief.

With thanks to Vincent Broqua and Olivier Brossard.

|

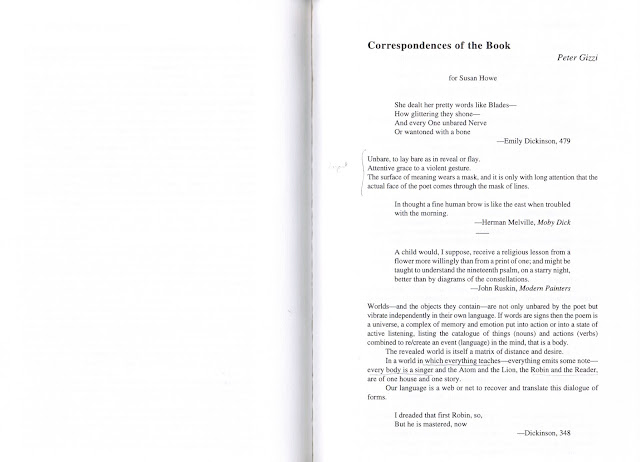

| Detail from L. E. Fournier's Funeral of Shelley, 1889 |